18 Sep 2024

Through the summer, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has articulated its worries about weak deposit growth, the rising credit-to-deposit ratio, and compositional shifts (too much unsecured lending, too few sticky deposits) that could hurt financial stability.

Many reasons have been attributed to weak deposit growth. But most of them do not stick. Strong inflows into mutual funds could not have cannibalised deposits, as the money stays within the banking system (even if it switches accounts). Currency leakage can’t explain weak deposit growth either, because the ratios have been moderating.

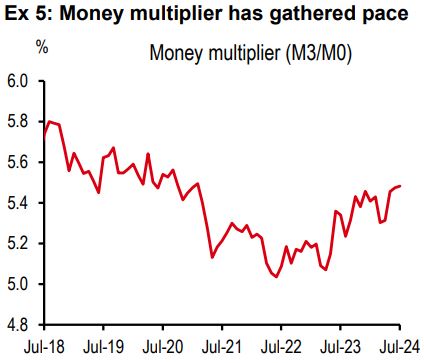

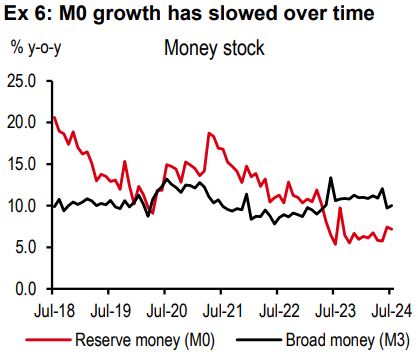

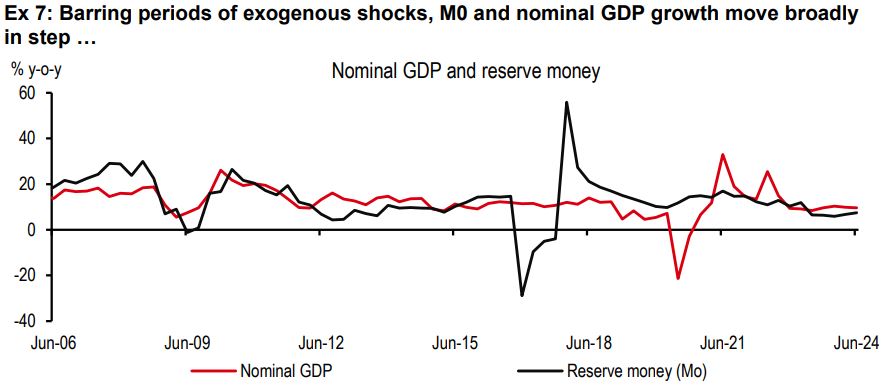

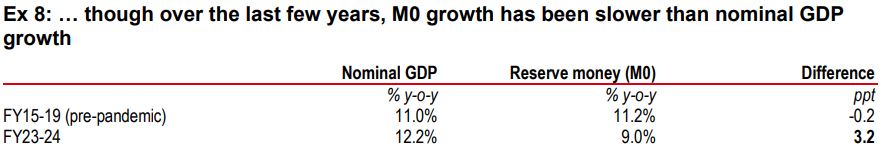

Then what explains it? Deposits have two creators – money created by the central bank (known as base money, M0), and money created by the commercial banks (through the money multiplier process). The money multiplier can’t explain the weakness. Rather, the multiplier has gathered pace over the last few years. So then, the weakness in deposits must come from M0 growth. And, indeed, M0 growth has slowed over time, even running below nominal GDP growth.

Why would the central bank slow M0 creation? For most of the last two years, inflation has been elevated, the dollar has been strong, and the RBI has been running tight monetary policy – raising rates with a hawkish “withdrawal of accommodation” stance, which is associated with tight liquidity. Meanwhile, delays in government spending due to the new just-in-time accounting framework have also kept liquidity tight.

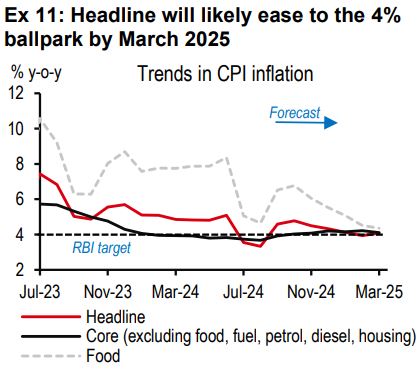

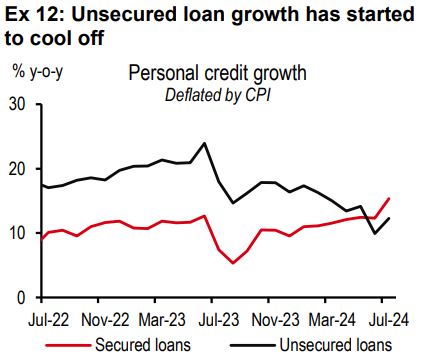

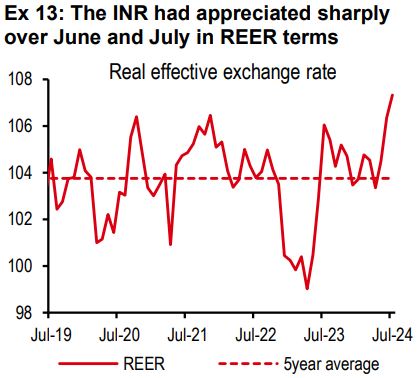

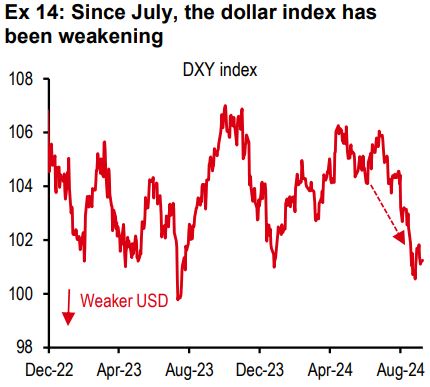

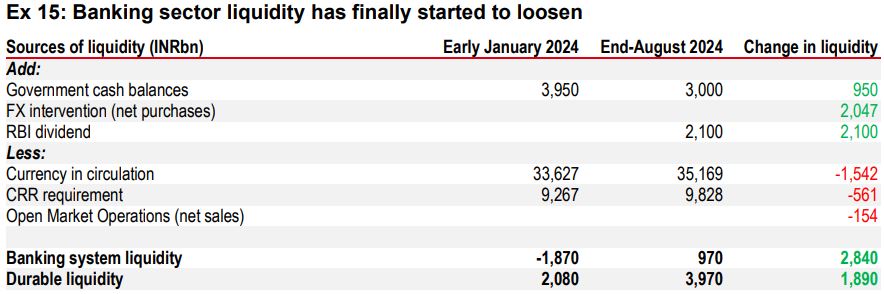

But all of this has changed recently. With the heatwave ending, inflation is converging towards target as per our forecasts, unsecured lending has cooled off, the dollar index has weakened in recent weeks, the RBI’s FX reserves have risen, and the government has ramped up spending. Some of these factors have arguably made the RBI more comfortable with faster M0 growth, while others have already raised M0 growth and eased banking sector liquidity in recent weeks. If this sticks, deposit growth could begin to tick higher, resolving half of the RBI’s worry.

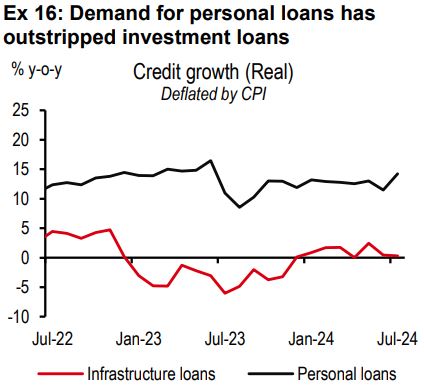

However, it may be harder to resolve the composition issue. With rising profitability, corporate saving has risen, resulting in higher callable bulk deposits, while household financial saving has moderated, resulting in weaker sticky deposit. All parts of the economy are not doing equally well and higher corporate profitability in some sectors coexists with weaker mass consumption. The latter has kept private investment and demand for capex loans softer than personal loans (some of which are unsecured). Addressing the two-speed economy issue with reforms will thus be key to resolving the other half of the RBI’s worries sustainably.

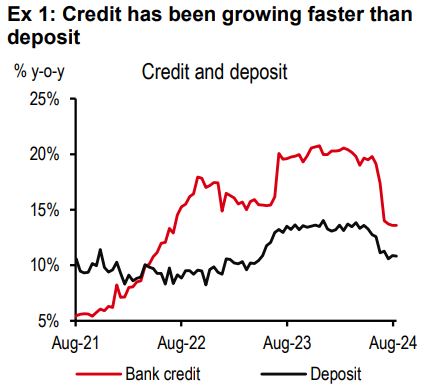

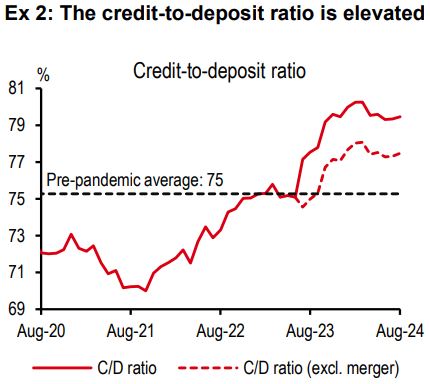

It’s been a long summer, with policymakers, especially the RBI, articulating at various forums over the last few months, its worries around the imbalance between deposit and credit growth at India’s banks. Credit has been growing faster than deposit growth for the last 30-odd months (see Exhibit 1). No surprise that the credit-to-deposit ratio is elevated (around 80% versus a pre-pandemic average of 75%, see Exhibit 2).

Why is this even a problem? An elevated credit-to-deposit ratio tends to autocorrect over time. And, already, there are signs of credit growth softening, leading to some moderation in this ratio.

The worries seem to be at a deeper level. It’s not just about the growth in deposit and credit, it is also the composition that is bothering the RBI.

On deposits, in the August policy meeting statement, the RBI’s governor said that “banks are taking greater recourse to short-term non-retail deposits and other instruments of liability ...”. This could “expose the banking system to structural liquidity issues.”

On credit, the RBI has been concerned about the rapid rise in unsecured lending. While that is gradually slowing, it continues to remain concerned about “excess leverage through retail loans, mostly for consumption purposes”.

In this report we drill into the root cause of this problem, and the connections with the RBI’s monetary policy stance. Thereafter we discuss when and how will this issue be resolved. We find that half the problem is already getting rectified as the RBI comes closer to softening its hawkish monetary policy stance.

The other half of the problem, namely the composition of credit and deposit, is more complex, with roots in India’s growth composition and saving behaviour, and will require ‘real economy’ intervention, a la economic reforms, rather than just financial nudges.

Let’s start with the weakness in deposit growth[@india-economics-09-01].

Many reasons have been attributed to this weakness. But most of them do not stick.

Are strong inflows into mutual funds cannibalising deposits? Not really. If one household takes out money from banks and invests it in mutual funds, some other household makes the underlying shares available, getting a cash deposit in return. Adding up across households, bank deposits remain unchanged. The same, broadly, can be argued for other financial assets like bonds, insurance products, and even property.

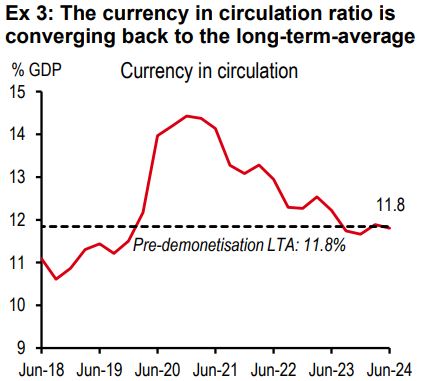

Is currency leakage hurting banking sector liquidity? Again, no. Because, as a percentage of GDP, currency in circulation has been declining back to pre-pandemic and pre-demonetisation levels (see Exhibit 3).

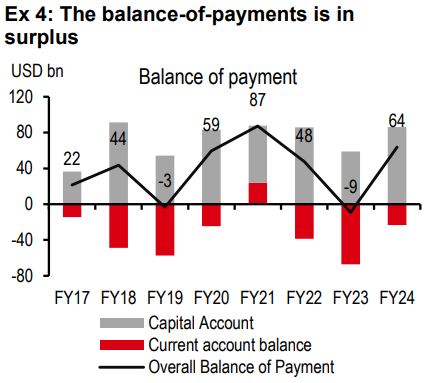

Is weaker foreign equity ownership leading to deposit outflow? Not at all. True that the ownership share of foreigners in India’s equity markets has fallen[@india-economics-09-02], while domestic participation has grown[@india-economics-09-03]. However, when we add up all the engagement India has with the rest of the world, across exports, imports, capital inflows and outflows, which is well captured by the balance of payments, we find it to be in surplus, and a growing surplus at that (from USD48bn in FY22 to USD64bn in FY24; see Exhibit 4), courtesy of strong services exports and portfolio debt inflows.

So, what’s really been driving the weakness in deposits? Let’s think through the monetary system carefully[@india-economics-09-04].

Taking a careful view of how monetary systems are interconnected, it is clear that deposits have two creators – money created by the central bank (known as base money, M0), and money created by the commercial banks (through the money multiplier process, i.e., the credit creation process).

And here, the money multiplier (calculated as M3/M0) can’t explain the weakness. Rather, the multiplier has gathered pace compared to the pre-pandemic period (see Exhibit 5). This is consistent with the strong credit growth over this period.

So then, the weakness in deposits must come from the weakness in M0, which the central bank creates[@india-economics-09-05]. And, indeed, it is clear that M0 growth has slowed over time (see Exhibit 6).

But why would the central bank slow M0 creation. Let’s dig deeper.

We believe a few factors influence the level at which the RBI wants to maintain M0.

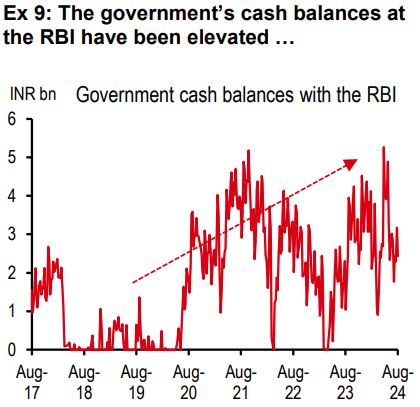

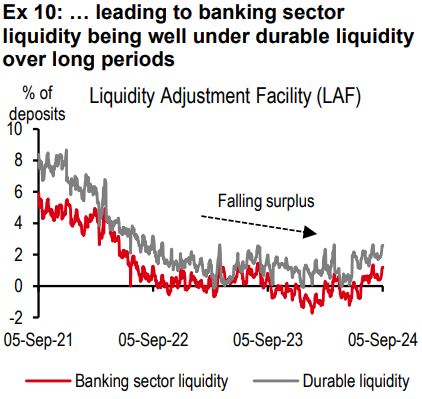

This has changed the government’s spending schedule; much of the spending now happens later in the year. And, while the money eventually gets spent, it first remains locked up for several months in a row (see Exhibit 9). This is clearly visible in the large gap between banking sector liquidity and core banking sector liquidity (which includes government balances at the RBI; see Exhibit 10).

To summarise, the weakness in deposit growth has been influenced by softer M0 growth, which, in turn, has been influenced by endogenous factors (like GDP growth and inflation, and the RBI’s objective regarding them), as well as exogenous ones (the government’s new just-in-time spending framework).

But this is a story of the past. It’s all changing quickly, as we speak.

There could have been a few reasons why the RBI kept M0 growth on the weaker side for the last few years. One, inflation was well above target, both in India and in the rest of the world. The RBI was hiking rates with a hawkish stance – a removal of accommodation. Two, the dollar was strong, leading the rupee into bouts of weakness. Arguably, the RBI had a preference for keeping monetary policy tight as an interest rate defence during this time. And three, credit growth was strong, and that as well, in areas the RBI was not comfortable with, like unsecured loans.

But each of these have now reversed quickly:

In fact, the RBI buying foreign exchange reserves and the government spending from its account at the RBI are ways to raise base money growth. Indeed, M0 growth has already risen from 5.8% y-o-y (over April and May) to 7.3% y-o-y (over June and July).

And, relatedly, banking sector liquidity has perked up in recent weeks, leading to market rates at the short end softening by 25bp (see Exhibit 10 above and Exhibit 15).

Yes, at least half of them. Let’s take them one at a time –

Deposit growth? Yes

With base money having risen recently and likely to rise further as the RBI moves from tight to neutral/loose monetary policy, deposit growth could get a shot in its arm.

Credit-to-deposit ratio? Perhaps

It’s harder to postulate whether the credit-to-deposit ratio will fall, as desired by the RBI. At first glance, if deposit growth rises, the ratio must fall. However, looking deeper, higher deposit growth could also make funds available for higher credit growth (assuming no fall in the money multiplier).

Composition of credit and deposit? Not so easily

Alas, this is where no quick solution seems visible. The RBI has been concerned about compositional shifts. Too much unsecured lending on the credit side. And too few sticky deposits and too much callable bulk deposits on the deposit side.

Some short-term interventions have helped and could continue to help. For instance, higher risk weights since November 2023 have lowered the pace of unsecured loan growth already.

However, these would be partial fixes. The reason the composition has gotten skewed lies in the real economy and will require real economy fixes, not just some financial nudges.

On the credit side, demand for personal loans has far outstripped demand for, say, capex loans (see Exhibit 16). Private capex is not firing on all cylinders. Investment in machinery and equipment is weak. Weak mass consumption is likely coming in the way of factories adding capacity. As such, weak mass consumption is the problem that needs fixing to change the composition of credit.

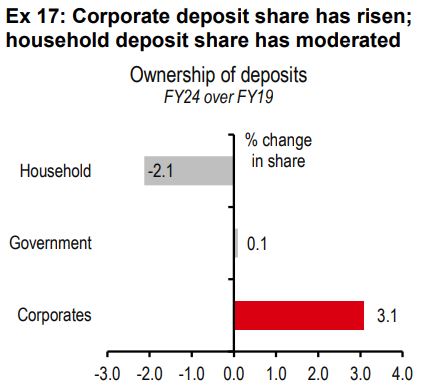

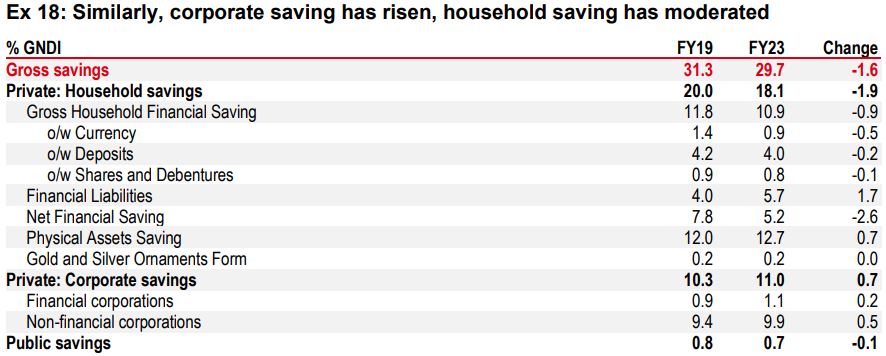

On the deposit side, there is a noticeable rise in corporate deposits and a fall in household deposits (see Exhibit 17). This maps well with India’s saving data, whereby corporate saving is above pre-pandemic levels, driven by strong profitability in certain sectors, while net household saving is lower than before (see Exhibit 18)[@india-economics-09-06].

This is partly reflective of a two-speed economy where some sectors are growing well, but all the gains are not flowing down to mass incomes.

In short, to improve the composition of credit (more capex loans, less personal loans) and deposit (more retail-led CASA deposits, less corporate bulk deposits), the economy needs to support income growth across the pyramid (low-, mid- and high-tech sectors).

This will require careful and timely reforms. One of them being making the most of global trends whereby many companies are trying to rejig production supply chains. Actively pursuing FDI in low- and mid-tech sectors like textiles, food processing, and toys, which tend to be more labour intensive, could raise both investment, as well as wages and incomes.

Additional disclosures

1. This report is dated as at 13 September 2024.

2. All market data included in this report are dated as at close 12 September 2024, unless a different date and/or a specific time of day is indicated in the report.

3. HSBC has procedures in place to identify and manage any potential conflicts of interest that arise in connection with its Research business. HSBC's analysts and its other staff who are involved in the preparation and dissemination of Research operate and have a management reporting line independent of HSBC's Investment Banking business. Information Barrier procedures are in place between the Investment Banking, Principal Trading, and Research businesses toensure that any confidential and/or price sensitive information is handled in an appropriate manner.

4. You are not permitted to use, for reference, any data in this document for the purpose of (i) determining the interest payable, or other sums due, under loan agreements or under other financial contracts or instruments, (ii) determining the price at which a financial instrument may be bought or sold or traded or redeemed, or the value of a financial instrument, and/or (iii) measuring the performance of afinancial instrument or of an investment fund.

This document is prepared by The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited (‘HBAP’), 1 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong. HBAP is incorporated in Hong Kong and is part of the HSBC Group. This document is distributed by HSBC Continental Europe, HBAP,HSBC Bank (Singapore) Limited, HSBC Bank (Taiwan) Limited, HSBC Bank Malaysia Berhad (198401015221 (127776-V))/HSBC Amanah Malaysia Berhad (200801006421 (807705-X)), The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, India (HSBC India), HSBC Bank Middle East Limited, HSBC UK Bank plc, HSBC Bank plc, Jersey Branch, and HSBC Bank plc, Guernsey Branch, HSBC Private Bank (Suisse) SA, HSBC Private Bank (Suisse) SA DIFC Branch, HSBC Private Bank Suisse SA, South Africa Representative Office, HSBC Financial Services (Lebanon) SAL, HSBC Private banking (Luxembourg) SA and The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited (collectively, the “Distributors”) to their respective clients. This document is for general circulation and information purposes only. This document is not prepared with any particular customers or purposes in mind and does not take into account any investment objectives, financial situation or personal circumstances or needs of any particular customer. HBAP has prepared this document basedon publicly available information at the time of preparation from sources it believes to be reliable but it has not independently verified such information. The contents of this document are subject to change without notice. HBAP and the Distributors are not responsible for any loss, damage or other consequences of any kind that you may incur or suffer as a result of, arising from or relating to your use of or reliance on this document. HBAP and the Distributors give no guarantee, representation or warranty as to the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this document. This document is not investment advice or recommendation nor is it intended to sell investments or servicesor solicit purchases or subscriptions for them. You should not use or rely on this document in making any investment decision. HBAP and the Distributors are not responsible for such use or reliance by you. You should consult your professional advisor in your jurisdiction if you have any questions regarding the contents of this document. You should not reproduce or further distribute the contents of this document to any person or entity, whether in whole or in part, for any purpose. This document may not be distributed to any jurisdiction where its distribution is unlawful.

The following statement is only applicable to HSBC Bank (Taiwan) Limited with regard to how the publication is distributed to its customers: HSBC Bank (Taiwan) Limited (“the Bank”) shall fulfill the fiduciary duty act as a reasonable person once in exercising offering/conducting ordinary care in offering trust services/business. However, the Bank disclaims any guaranty on the management or operation performance of the trust business. The following statement is only applicable to by HSBC Bank Australia with regard to how the publication is distributed to its customers: This document is distributed by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162, AFSL/ACL 232595 (HBAU). HBAP has a Sydney Branch ARBN 117 925 970 AFSL 301737.The statements contained in this document are general in nature and do not constitute investment research or a recommendation, or a statement of opinion (financial product advice) to buy or sell investments. This document has not taken into account your personal objectives, financial situation and needs. Because of that, before acting on the document you should consider its appropriateness to you, with regard to your objectives, financial situation, and needs.

Important Information about the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, India (“HSBC India”) HSBC India is a branch of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited. HSBC India is a distributor of mutual funds and referrer of investment products from third party entities registered and regulated in India. HSBC India does not distribute investment products to those persons who are either the citizens or residents of United States of America (USA), Australia or New Zealand or any other jurisdiction where such distribution would be contrary to law or regulation.

Mainland China In mainland China, this document is distributed by HSBC Bank (China) Company Limited (“HBCN”) and HSBC FinTech Services (Shanghai)Company Limited to its customers for general reference only. This document is not, and is not intended to be, for the purpose of providing securities and futures investment advisory services or financial information services, or promoting or selling any wealth management product. This document provides all content and information solely on an "as-is/as-available" basis. You SHOULD consult your own professional adviser if you have any questions regarding this document.

The material contained in this document is for general information purposes only and does not constitute investment research or advice or a recommendation to buy or sellinvestments. Some of the statements contained in this document may be considered forward looking statements which provide current expectations or forecasts of future events. Such forward looking statements are not guarantees of future performance or events and involve risks and uncertainties. Actual results may differ materially from those described in such forward-looking statements as a result of various factors. HSBC India does not undertake any obligation to update the forward-looking statements contained herein, or to update the reasons why actual results could differ from those projected in the forward-looking statements. Investments are subject to market risk, read all investment related documents carefully.

© Copyright 2024. The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, on any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited.

Important information on sustainable investing “Sustainable investments” include investment approaches or instruments which consider environmental, social, governance and/or other sustainability factors (collectively, “sustainability”) to varying degrees. Certain instruments we include within this category may be in the process of changing to deliver sustainability outcomes. There is no guarantee that sustainable investments will produce returns similar to those which don’t consider these factors. Sustainable investments may diverge from traditional market benchmarks. In addition, there is no standard definition of, or measurement criteria for sustainable investments, or the impact of sustainable investments (“sustainability impact”). Sustainable investment and sustainability impact measurement criteria are (a) highly subjective and (b) may vary significantly across and within sectors.

HSBC may rely on measurement criteria devised and/or reported by third party providers or issuers. HSBC does not always conduct its own specific due diligence in relation to measurement criteria. There is no guarantee: (a) that the nature of the sustainability impact or measurement criteria of an investment will be aligned with any particular investor’s sustainability goals; or (b) that the stated level or target level of sustainability impact will be achieved. Sustainable investing is an evolving area and new regulations may come into effect which may affect how an investment is categorised or labelled. An investment which is considered to fulfil sustainable criteria today may not meet those criteria at some point in the future.